The world of sex work has been the subject of movies for decades, whether told in coded language or given a documentary-like realism. In the wake of the Best Picture-winning Anora, audiences expect a humanist portrayal of this profession on the margins of everyday society, rather than the exploitative material often found in prestigious dramas of the past. Before Sean Baker converged the absurdist mania and sobering realities of sex work in 2024, the great satirical filmmaker, Luis Buñuel, pulled back the curtains of this world and portrayed it with his brand of surrealism in Belle de Jour. Starring the legendary French actor Catherine Deneuve in one of her signature performances, the 1967 dark drama highlights the perversely alluring sense of independence provided by sex work while dampening these fantasies with the despair it brings to its inhabitants, from a sociological and psychological perspective.

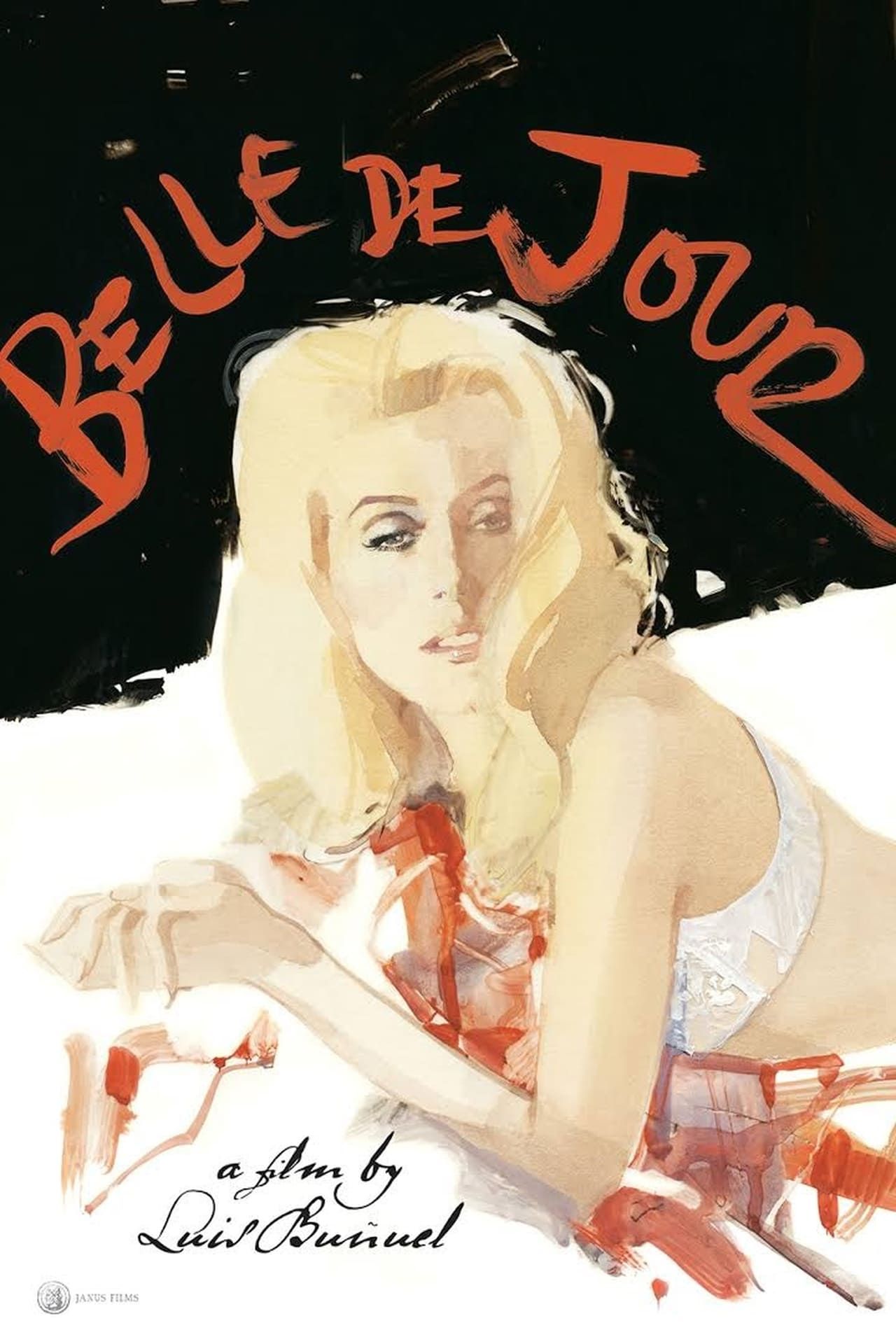

Luis Buñuel Directs Catherine Denevue’s Most Impressive Performance in ‘Belle de Jour’

A Spanish and Mexican filmmaker who frequently worked in France, Luis Buñuel’s multinational background was transmuted into his eclectic filmography. When he transitioned into surrealist filmmaking in the 1960s, the Buñuel that we celebrate today— a daring artist who tackled pressing social and political commentary with an avant-garde touch, most notably in his most acclaimed film, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie—was fully formed. Buñuel is frequently cited as a seminal influence on your favorite contemporary filmmakers, particularly Wes Anderson, whose own idiosyncratic, highly expressive formalist style owes a lot to his bold aesthetic.

As previously mentioned, cinema tends to glamorize or degrade those who participate in sex work. One could argue that Pretty Woman, which patronizes the lifestyle with the trope of the “call girl with a heart of gold,” is just as retrograde as Leaving Las Vegas, which leans into its downtrodden nature and ultimately disposes of its characters. Across a variety of eras, genres, and subjects, such as pornography and striptease establishments, Hollywood and international cinema have been trying to exploit or, in the best cases, understand the liberation and plight of the trade.

Belle de Jour operates as a psychological examination of the illicit world of sex work, and it posits that the line of trade brings many of the same feelings of aimlessness as our everyday lives. The film follows the titular “beauty of the night,” Séverine (Deneuve), the wife of a doctor, Pierre (Jean Sorel), who spends her midweek afternoons moonlighting as a high-class escort while her husband is at work. Without a towering performance by Deneuve, who emerged as a striking ingénue in the musical, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, and Roman Polanski‘s psychological horror-thriller, Repulsion, Belle de Jour would lack its fine-tuned balance between sensitivity and exploitation. Deneuve upends all expectations of beautiful leading ladies who are asked to adhere to traditional feminine expectations without upsetting the status quo. As Séverine, she embodies cinema’s complex relationship to sex work, expressing equal amounts of lustful intrigue and dread towards working at a brothel for abusive men.

‘Belle De Jour’ Reflects the Distorted and Complicated Psychology of Sex Work

As a surrealist filmmaker, Buñuel distorts the reality of the film through the lurid desires woven into our psychology. The film doesn’t run away from the eroticism of this profession, and Buñuel’s sharp direction underscores why people want to submit themselves to this world—to feel something otherworldly by partaking in this everyday, oftentimes mundane, activity. The film abruptly flashes back to traumatic moments in Séverine’s youth where she appears to be abused. Rather than existing as exposition to solve the mystery of this inscrutable character, these memories flash onto the screen frantically and without narrative cohesiveness. Buñuel’s surrealist approach to the form indicates that Séverine was lured into this world of lurid sexuality by her own haunted memories and/or nightmares. If we can’t understand her plight, especially since she lives a comforting domestic life and is by no means in a desperate state like most cinematic sex workers, that’s only because she’s lost sight of herself.

Related

15 Movies To Watch if You Love ‘Anora’

“You know why this is my favorite tree? ‘Cause it’s tipped over, and it’s still growing.”

The class commentary and marital strain stemming from general ennui are quintessential Buñuel, an abstract director who manages to sneak in direct and pressing satirical talking points relating to contemporary society. The alienation of people trapped within the confines of societal expectations, Séverine as a domestic caretaker and Pierre as the financial provider, is a surface-level theme that helps the viewer engage with the text, but Belle de Jour‘s satirical chops arise in its challenging depiction of female archetypes. A demanding proposition in 1967, Buñuel forces the audience to shatter their “Madonna-whore complex” relationship with a woman’s sexuality. Séverine wants to support her husband, herself as a liberated person, and appease her inner demons, which may or may not have sadomasochistic intentions.

Films set in the milieu of sex work tend to be didactic, but Belle de Jour encourages endless viewer interpretation and judgment of this profession. Thanks to hypnotic editing rhythms and camera work by Luis Buñuel and an emotionally all-encompassing performance by Catherine Deneuve, the film should be your companion viewing to Anora.

- Release Date

-

April 10, 1968

- Runtime

-

101 Minutes

- Director

-

Luis Buñuel

-

Catherine Deneuve

Séverine Serizy

-