Summary

- Collider’s Steve Weintraub talks with Malta film commissioner Johann Grech and Hollywood production designer Rick Carter at the 2025 Mediterrane Film Festival.

- During this interview, Grech discusses plans to expand filmmaking in Malta, the soundstage currently in the works, and continuing to grow the Mediterrane Film Festival each year.

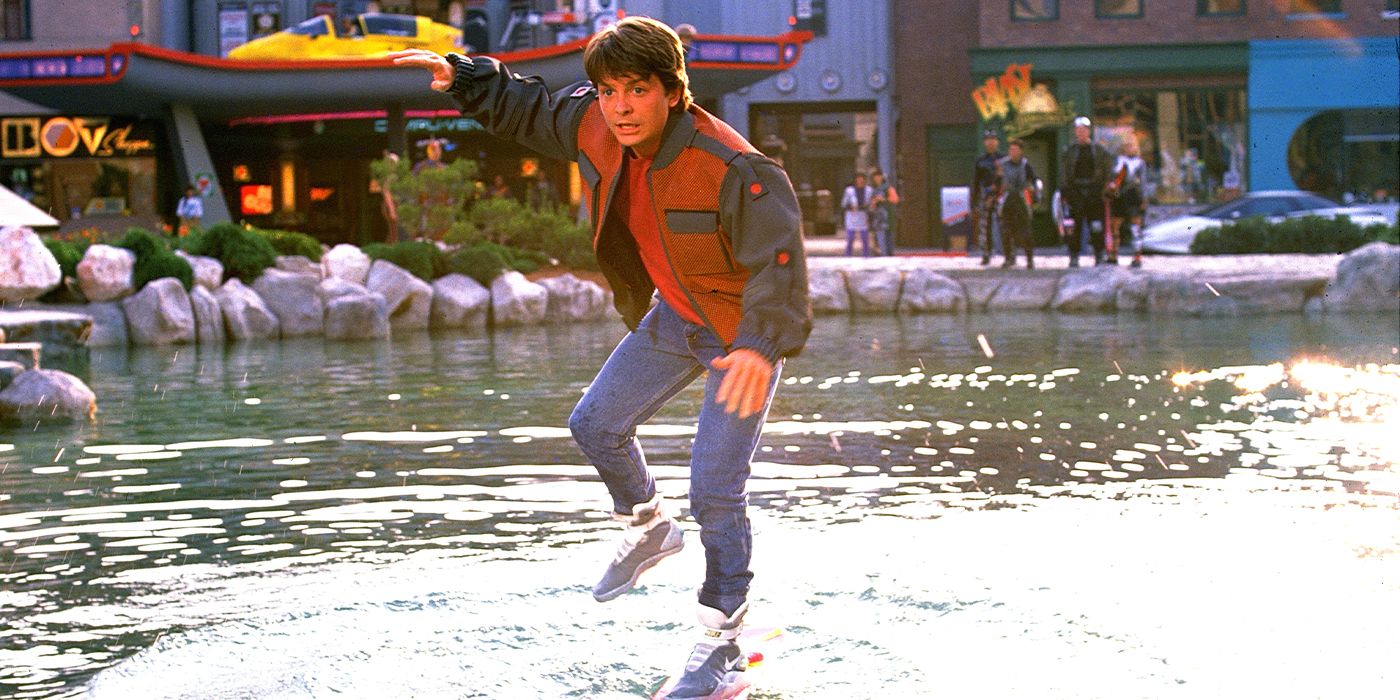

- Carter discusses working with Steven Spielberg, Robert Zemeckis, and more on iconic movies like Jurassic Park, Back to the Future Part II, and The Goonies.

At the third annual Mediterrane Film Festival, held on the island nation of Malta, Collider’s Steve Weintraub had the esteemed pleasure of sitting down with Film Commissioner and CEO of Malta Film Studios Johann Grech and Hollywood production designer and art director Rick Carter for an in-depth conversation about filmmaking and expanding the horizons of cinema beyond Tinseltown.

In just under a decade, Grech has made it his mission to put Malta on the moviemaking map, turning the remarkable island into a hub for productions to stake out breathtaking locations, and for the Mediterrane Film Festival to offer cinephiles and studios the chance to step back in time. During their conversation, Grech shares the pride and plans he has for the growing film festival, and discusses why building a “world-class soundstage” in Malta will cement the nation’s position as a production must.

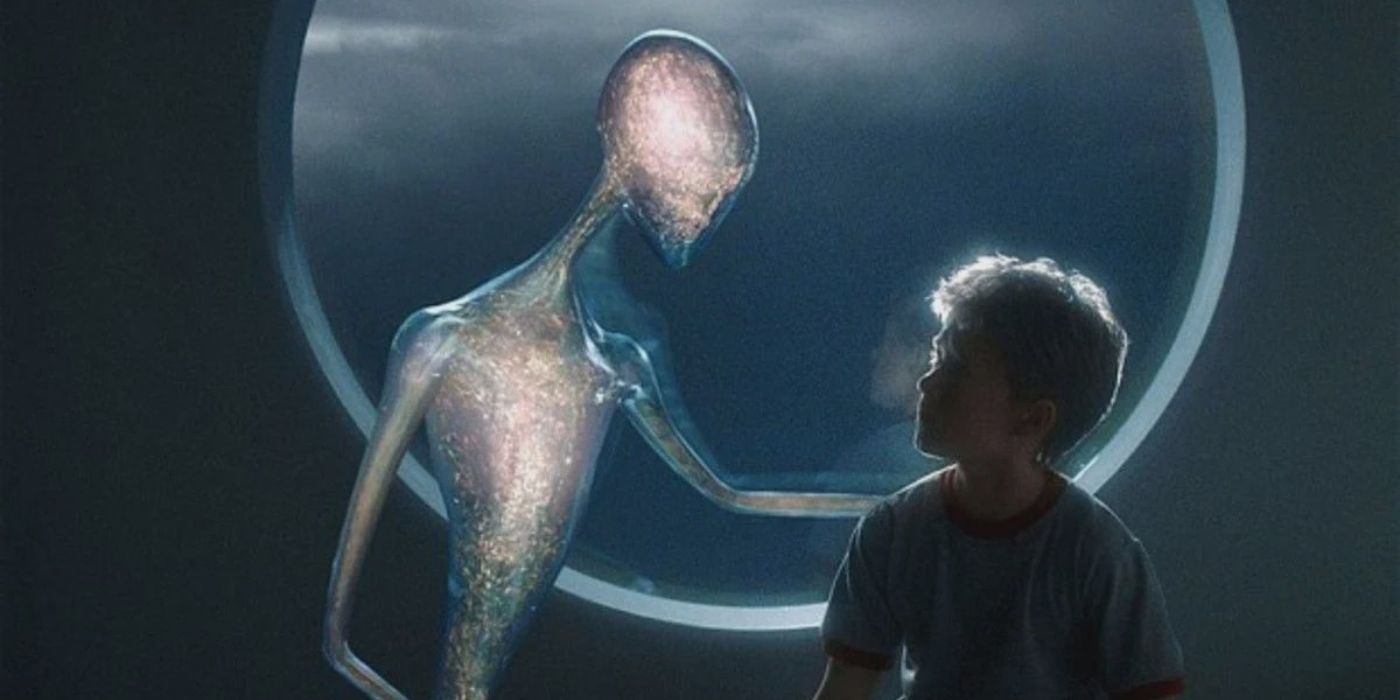

Collider also goes behind the scenes with Carter, whose career launched after serving as art director under the tutelage of Richard Donner and Steven Spielberg on The Goonies. After 1987, Carter took on the role of production designer for Robert Zemeckis on Back to the Future Part II, before working his movie magic on the sets of Death Becomes Her and reuniting with Spielberg for Jurassic Park. In this interview, Carter shares tales about practical dinosaur design with the likes of ILM and Phil Tippett, what it truly means to be a Goonie always and forever, how he designed the future in Back to the Future Part II, and what it was like watching Spielberg bring Stanley Kubrick‘s original vision for A.I. Artificial Intelligence to the big screen.

Rick Carter Demystifies the Role of Production Designer

Carter has worked alongside Steven Spielberg, Robert Zemeckis, James Cameron, J.J. Abrams, and more.

COLLIDER: A lot of people hear the term “production designer” or “visual concept artist” or “film commissioner,” and know the words and think they know what it actually means, but can you explain to people what a production designer does? What does a concept artist do? The positions you’ve done in Hollywood, what do they actually do? For you, as the Malta film commissioner, what does it actually mean to be the film commissioner of a country?

RICK CARTER: [Laughs] I want to I want to be able to say, “I actually have no idea,” and part of the reason is because when I got into doing production design in the very beginning, back in 1974, my mentor, who was one of the top production designers at the time, Richard Sylbert, who worked on movies like Chinatown and big hits at the time, he said, “No one’s ever going to know what you do.” Here I am all these years later, and it’s the big question, of course: well, what does the production designer do? For me, it’s seriously been a journey of discovery, each film, to make my role something that’s important with the director in terms of how they stage their movie, how they create the worlds, and the ideas that are in the movie. So, I’m constantly in an evolving process.

Of course, physically I have to be responsible for the sets; digitally, I have to be responsible for the look of the extensions and the overall feel of it, but it’s not something that people who don’t make movies really can see. You can hear about it, and it’s kind of interesting to see a set being built, yeah, yeah, yeah — but who’s in it? What’s it about? That’s all you want to know. So, my job and the art department is to explore a subject, make it as rich and detailed and authentic as possible, and something that the director and the actors and cinematography can all work with in order to create an illusion that you believe, that you believe you’re somewhere and you’re not.

I don’t think people realize how long your job lasts. Some people come on to set when filming begins, the filming ends, and they’re done. With you, I’ll use Munich as an example because it was filmed here in Malta. How early on do you get on a project, and how long are you on after production wraps?

CARTER: If I was just taking Munich as an example, which is a little bit different in that it’s a location-based movie for the most part, I was on actually the first time, two and a half years before the movie was made, because I went out to look for the locations in Europe, and how to create 14 different countries. The solution turned out to be to come to Malta to do half of the movie and make seven different countries here. But it took going to the various places that the movie is supposed to be set in the 1970s, and then understanding how to do it economically, but also to get a look that was unique, and it would be new, and Malta provided that. But I was on for a long time.

Then the movie was shut down. So then we went on to other things for a while, and then it came back. Then I joined the production again. But often it’s at least nine months on the prep and the shoot, and then often into post, I’m called in not on full time all the time, but a lot of it to go all the way through to make sure the look that we’ve established in the beginning is being carried over, and that the ideas are still there and not put through so many different people that you lose sight of what’s important.

Malta Film Commissioner Johann Grech Is Turning the Industry Around

“This has been a success story.”

Let’s talk about being a film commissioner. Talk about what being the Malta Film Commissioner actually means. What does the job entail?

JOHANN GRECH: Basically, the job is to get business to Malta, and also to get inward business towards our country, building, also, the crews, and making sure that we have a strong product. The primary aim of the film commissioner is to get business to Malta and also to strengthen the brand image of Malta in terms of the film industry on the global stage. So, basically, it’s marketing, too. Under my administration, I have been commissioner for a little over seven years, and we strengthened our product, we developed our product, we increased our tax rebate to 40%, and we also lobbied the government to put further investment towards film infrastructure. In fact, today we are on the doorstep of reaching out investors to build the first sound stage in Malta, which would be a world-class sound stage. Also, we saw the industry from a seasonal one into not just back-to-back, but an industry working every day all year round. Today, we have over 1,000 local crew working in film in Malta all year round. Eight out of 10 of the crew, we can confirm, are Maltese. So, the biggest challenge was to turn the industry from a seasonal one to an industry working all year round, and I think that we have achieved it.

If you could go back in time to when you first started as a film commissioner, what would you tell yourself that you’ve learned? Because on every job that you do, you learn and you pivot into what’s coming. What are some of the big lessons you’ve learned over the seven years that you wish you almost had started sooner, or do you think you couldn’t start sooner because each year has built to where you are now?

GRECH: I wasn’t afraid of challenging the status quo and changing things. For me, change is a process, not an ending. So, it was a journey. We continue to build our vision based on the experience gained. But looking back, and this is one of my biggest satisfactions of the job, we turned the industry completely. We are celebrating today 100 years of film in Malta, and the last five years were the best years ever. In the last five years, the industry generated over a billion into our economy. 2023 was the best year ever for film in Malta. We were 18% of the economic growth of our nation, one-sixth. That means that we created more jobs. We sustained 15,000 jobs in Malta. This has been a success story, and a success story because we have worked together. We had a resilient strategy, and it worked.

“Once a Goonie, Always a Goonie”

Rick Carter takes us behind the scenes of one of the most influential adventure films of the 1980s.

Rick, I have to bring up a past project with you because one of my all-time favorite films is The Goonies, and you did work on The Goonies as an art director. What do you remember about making that film?

CARTER: Well, I’m a Goonie. I was a Goonie then, and I’m a Goonie now. It was the decisive experience as a young man in my early 30s to work with Michael Riva, with the production designer, and Dick Donner and Steven Spielberg. If I look at the amount of life and interest and just Gooniness that got into me… I’ll explain what I mean by that. I’m 75, so if I’m talking you and saying I’m a Goonie, what does that mean? It sounds cute, but I’ll just go through a few riffs because it’s the experience.

First of all, it’s where I met Steven Spielberg because he was the person who wrote the story, was the executive producer, and was the second unit director. When he came over to look at the sets, the production designer, Michael Riva, who was a good friend and fantastic mentor, and Dick Donner, who was a wonderful director, were often location scouts. So, I took Steven and Kathy Kennedy, his producer, around the soundstages, but I did it in the order of the movie. I started with the lighthouse and went down underneath to the level below — these were on different soundstages — and then to the cave of the pipes, and through all the Rube Goldberg contraptions to get to, voila, the ship, and there is the ship that we built. It really was fun to show Steven, in a narrative order, the progression of his story. He hadn’t seen any of it.

And I think that’s why he took some of the attention to who I was and offered the amazing stories to me, and then I’ve done 11 movies with him since then. So, that’s a pretty big moment where we were sharing our Gooniness. Then I was covering all of his work as second unit director, so we had lots of dialogue back and forth and got to know each other. We’re not that far apart in age. I’m three years younger; he’s like an older brother. At the same time, I was aware that he had done so much and was doing so much. Michael and I were like these two kids in a candy shop, making all this stuff.

I had this epiphany on the movie, which was: I was coming up over the hill, driving to work into the Valley, and I actually had that fear factor that you can have, of course, in making any movie, but as a young person, I realized we don’t know what we’re doing. This is really difficult to make this ship, the caves, and everything, and on time. We were really pushing the boundaries because in those days, studio work had been condensed to mostly location kinds of movies. So I was thinking, “God, I don’t know how we’re going to do this.” And then I had this light bulb go out literally as I was cresting Mulholland in Los Angeles, and I thought, “If I was 10 years old, I would want this movie. I’d want to do this job. I would want to be a swashbuckler — paid to be a swashbuckler. I’m not doing my father’s work another generation. This is ours.” That’s the Gooniness. That’s when you recognize. It’s even in the theme of the movie, which is, “This is our time down here. This is not the time that’s being controlled by the adults or the restrictions of reality.” Instead, for me, that was a kind of experience that we all knew we were having, and we were leading to this treasure that would be taken away, but you have just enough to save the day.

So, that kind of Goonies adventure along the way got deeply into me, and that’s the way I’ve approached every movie since, and particularly with Spielberg, but also with Bob Zemeckis, Jim Cameron, these adventures that I get to go on. And I’m a believer. I get in there like, “We’re really living it.” So, I always enjoy answering a question about Goonies because so many people of a certain age took it in, and I think they took it in in a way, not watching it necessarily on a big screen but at home on either a video or a disc, and you were so young, your parents let you just go watch it, and you’d watch it episodically, or parts of it, and it just gets in there, and you go, “I want to be like that.” I think that’s the biggest single thing that I’ve gotten to experience as a filmmaker, is the wish fulfillment of, “I want that,” and then I get to do it. Particularly if you’re with the right people and if they’re treating you well, it’s all the better. So, for me, that’s what being a Goonie is, and I love being a Goonie at this old age. [Laughs]

Related

Will ‘The Goonies Cast Return for the Sequel? “Keep the Adventure Alive”

The original creative team is involved in the sequel.

That film has really stood the test of time, but more than that, it’s crazy that Spielberg did second unit on that film.

Malta Embodies the Essence of What Filmmaking Is

The Mediterrane Film Festival captures the spirit of collaboration.

So, we’re in Malta, and you obviously shot here 21 years ago with Munich, but you’re on the jury now of the Mediterrane Film Festival. What is it like coming back to Malta 21 years later and being on the jury of a brand-new film festival?

CARTER: I actually wouldn’t mind, especially since you’re here, and Johann has put this together, but for both of you, to just do a little riff, which is kind of my methodology for being creative, on what I’ve experienced here. My father was in public relations, so I’m not unaware of what it is to take the essence of something that you’ve done and try to bring it up as not the brand, but a way to identify it, but in a way that it draws you in as to where are you and what’s going on. So, in Malta, the spirit of place here is very, very strong, and what I mean by that is the history that has come through and been a part of this island, both generated from it and come to it, all the people that have landed on this island, that’s a pretty amazing group of people throughout history. But it’s not even just that simple.

Here goes the visual riff for what we’re doing, where we are, what the jury is doing with us picking from all these films, and there are so many good films. This is an island in the middle of the Mediterranean. There’s no other island in the middle of the Mediterranean that takes from all these areas around, the continents. It depends on where you want to start. You can start with Greece and go to Cyprus, down to Lebanon and Israel, and Palestine. Where else can you go and say, “This is where I am, and this is what’s around me?” And it’s a sea. It’s moving all the currents from all these places, and they keep going across North Africa from Egypt, all the way to Tunisia, Morocco, and come back up to Spain, and then you hit France, Italy. The influences, these civilizations, and then what comes here, you have the ability to take all that influence, and there’s no place like it that takes all of that in, and then can actually be a place that reflects it back out with unique character to the world. That’s actually what this selection of movies is like that we looked at.

We went in to jury for three days, saw 10 movies, just immersed in this world of cinema. The variety and the depth and the vitality of the cinema that’s this generated feels like literally a bit like, “What’s going on there in Malta? What is that?” That’s a lot of cinematic visual storytelling that’s of a very distinct culture because it’s a mixture. It’s a hybrid. And so much of what we are dealing with in the world now is how do you combine so many disparate elements? So, that’s really happening here. The waters carry that information. The winds carry that information. It’s been happening for thousands of years. You can even find places here that reflect that, and you can add them in a movie, and even say that there’s something else, like we did in Munich, where we actually picked places, but we made it into seven different Mediterranean countries.

GRECH: I totally agree with your analysis. Malta has always been a bridge between continents. When we came up with the idea of developing the Mediterrane Film Festival, it is also a bridge to other countries, to other nations, to collaborate together. Because at the end of the day, film is about collaboration. It’s about reaching out and discussing ideas and developing ideas, and co-producing stories. So yeah, I completely agree with your analysis.

CARTER: There’s a dynamic that I’m aware of because, being a production designer, it literally is my purview and job to find the place for the movie or to create the place. If you create it, you have to think about what makes it authentic and believable to the story, not just what it is. I’m not a tourist looking at everything for what it actually is. I’m looking for, “Well, how does Kauai in Hawaii serve being a place that can become the home for the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park?” Or to how then create something like that when the Avatar would never actually go to a jungle? But here, what you have is all of these. It’s rock, it’s stone, it’s lives, it’s culture. The room we’re in, things happen here. We’re having this discussion, but the vision, if you just think about what’s in the air that comes from being creative or having thoughts, even if you were planning a campaign here to go out and conduct war, the idea or defense, the idea that some place generates that kind of energy, that’s what’s at the heart of cinema anyway.

We can talk about it on a million levels. I know I’m going a lot deeper than most people do, but I’ve been in this for a long time, and if I get to age 75 and still look at it as, “Oh, it’s just thin little sliver of, ‘Oh, look at the movies and how good are they this year? What’s the top ten?’” That’s just silly for me because I have a lifetime of investment and receiving from it. What I’m saying is that Malta has that kind of a feel to it for me, that I can see the depth. You can really walk by the fort walls, and you go, “How thick are those to function?” And that’s the way cinema is to me. It’s an ongoing generational hand-off from one person or generation’s dreams being expressed to the next. And I think there’s a lot here that comes together. The festival itself is reflective of that kind of storytelling.

Related

Zoe Saldaña Teases Neytiri’s Role in ‘Avatar: Fire and Ash’

The third installment in James Cameron’s franchise premieres next year.

One of the things that I always tell people back at home in Los Angeles is that when I walk around Malta, I feel like I’m walking back in time. I’ve gone on a number of the tours here, in terms of seeing the different things, and there’s a fort that was built in 500 A.D. or something crazy. As someone who loves history, it’s pretty crazy.

GRECH: Malta is a film set in itself. Take, for example, Munich doubling up for six or seven different countries at the same time, which shows the level of versatility of locations that we can offer.

It’s also why I think Ridley Scott films here so much. You think about the Gladiator movies or Napoleon. There’s obviously set deck that you have to do. If you were filming in here, you’d have to do some set deck, but the bones are here. You don’t have to put up a wall. You just have to decorate a little bit.

CARTER: Absolutely.

Travel Back in Time to the Set of Steven Spielberg’s ‘Jurassic Park’

“My god, we’re bringing these things back to life.”

Some of the recent Jurassic World films have been filmed here, but you worked on the original Jurassic Park. When you were making Jurassic Park, obviously it is coming off of a huge book and it’s Spielberg, and you know that this could be really good, but at what point did you realize, “Oh, this could be the game-changer?” For some people, this is their favorite movie of all time. It revolutionized sound and visual effects. It’s a monster of a movie. It changed Hollywood.

CARTER: Well, it was a book at first, of course, by Michael Crichton. When I came onto the project, there were the galleys of the book. The book had not been released yet, but it had gone through a bidding war that Steven and Universal had won, so they had the rights to do it. So, Steven called me in early, and I had a team — that’s what the art department is, sort of a team of people that explore not only the content of it, but how to do it. So, with the content, the script had to be written, but we could go off the galleys to do some of the sequences, and Steven would then sit with us and we would talk about some of the sequences, like the introduction of the T-Rex, and how he would want to do that just visually.

How to technically do it was an evolving process that we didn’t know how deep it would go, because stop-motion was the way you would naturally, in that era, go, which is frame by frame by frame, physically. Phil Tippett was a master at doing that. But the computer was coming up, and Dennis Muren knew that, and the people at ILM knew the computer was being developed in such a way. Along with Steven’s OK, I was actually in the meeting when they gave the go-ahead to add the money to put the skin onto the bones of the dinosaurs. They’d shown a cycle to see, “Oh my god, I can actually make those bones look like a Ray Harryhausen movie. Very effective! How much to put skin on that?” That was Larry Stevens’ question. And the answer was $500,000. It was like, “Okay. Do it.” And that’s his money, actually, at that point, because that was the way his deal was constructed. It had a very specific budget that he was responsible for anything that went over that. He was interested in, really, not so much the technology, but bringing dinosaurs to life. Another dominant species on our planet — “Can I do that in the movie and make that credible?” Not just a monster movie, but in awesome awe of the dinosaurs, and instilling that kind of feeling into the production.

I think all of us realized that we were onto something when Stan Winston came into the picture and designed with his artists most of the dinosaurs, and then ILM brought the whole way of doing it in the computer into being. Then, Phil Tippett joined with Dennis Muren and ILM, and they gave him a rig so that he could do what he did with his hands, but it would input into the computer. So, Phil was still basically not only the master dinosaur wrangler, he would be like the dinosaur. He’s a wonderful person. If you’re in a session with him, you’re talking about, “Well, the raptors do this, or this will happen,” and then he’d be getting kind of antsy. Finally, he’d be like, “Listen, listen, I know you guys are all interested in what the humans are doing, but let me show you what those raptors are going to be doing.” And he would start to act out what the raptors are going to be doing because they’re in the movie, but somebody’s got to take care of who they are, not just, “I move from here to here and I’m a monster,” but, “What am I doing if I’m opening a door? I’m in a kitchen. It’s reflective. Have I ever seen a reflection before? I’m a raptor. I’ve never been alive other than in my time, where there was only water that would reflect anything.” I mean, these types of things went into our conversation, and you can imagine how interesting, not just intellectually, but how much you start to go, “My god, we’re bringing these things back to life.”

Then Steven was able to use the physical dinosaurs that Stan did, and then blend them with the digital so that there’s kind of a hybrid reality in the movie that I think still holds up quite well. But I think it’s the awe, and the believability, and then the actual wanting them to exist that pervades that movie. We all caught that. I was never a big dinosaur fan before that, but after helping to bring them to life and my part in it, and the staging of the park, I just thought, “This is a magical process.” Goonies was the legend. You learn it on The Goonies, and then you get to do some amazing stories, which were a lot of fun, with a lot of different directors. Then the first movie is Jurassic Park. I mean, it was Back to the Future, too. I’m not jumping, but I’m just saying, that explosion of imagination and optimism, and there are no rules. There are no roads.

The most important thing, I think, and Jurassic Park is a perfect example of it, is that it’s a film that blends physical effects with computers. It is the most effective because you look back on things from the ‘70s and the models, and they still look real because it’s physical.

The Jurassic World Films Have Had a Dino-Sized Impact on Malta

“It is a success story.”

The Jurassic World movies have meant a lot to Malta.

GRECH: Oh yeah. Twice.

Exactly. Talk a little bit about what these big Hollywood movies actually mean for a country like Malta. Are they coming in for two weeks, or are they coming in for a long time? What does it actually do for the local economy when this big crew comes in?

GRECH: It’s a huge impact. We need these big films here in Malta. Today, we can facilitate more of these big films because we have a strong crew base. Currently, as we speak, we have seven films shooting at the same time. When Gladiator II was shooting here, 96% of Gladiator II was shot here in Malta in 2023. At the time, we were servicing, also, five other films. So, back to Jurassic World Dominion, Malta was around 20 minutes on the big screen, so that impact, our impact is bigger. I mean, look at how many eyeballs saw Malta on the big screen.

But also, the ripple effects on our economy are so huge.

Then, the second Jurassic World, the reboot, the second one shot in Malta, and used Malta’s water tanks. Watching them again and again, you feel so proud that just a small island in the Mediterranean, a small country, but a great nation, the pride that we have in the film business is so huge. Looking at the impact, at the economic impact, looking at the jobs, looking at the business that it generates, it is a success story. That’s why we are investing more, because the investment that the government is doing in the industry, and we have a government that understands film business, the value of investment back is huge.

I want to talk a little bit more about this, if you don’t mind, because I live in Los Angeles, and Los Angeles has basically lost all production. Everyone’s filming around the world, which is because it’s more more incentivized, and I’m all for wherever the movies need to be made. Obviously, I would love more to be in LA, as well, but what people don’t realize and maybe the citizens of Malta don’t realize, and I can speak for this firsthand, is that when a big film crew is staying at the hotel, they’re eating breakfast and lunch and dinner in Malta, they are getting their laundry done in Malta, they are using the cars in Malta. The amount of money that permeates throughout the economy is massive, and I don’t think people realize.

GRECH: For example, for every euro that we invest in film, the industry generates three back into our economy. So, would you invest more? Yes, we will invest more. When you invest $5 million, you get $10 million. Would you invest $5 million to get $10 million? This is logic.

CARTER: The funny thing is, it obviously makes sense, and California can’t do it. And you’re kind of going, “Okay, well, stupid is as stupid does.”

GRECH: Before my time, it was a seasonal industry. You had a cycle: two years on, two years off, two years on, two years off again. Now, we’ve broken the cycle, and we had a huge rise. When we turned the industry from only 200 crew members, local crew, working for a limited time during the year, to now 1,000 working all year round, this is a success story. We were inspired by other nations, and I believe that now we are a model to other nations to follow and model, and we need to keep on strengthening our product because you can’t stop changing.

CARTER: And evolving.

GRECH: And evolving. So, that is key.

Related

He also talks about if they’ve thought about building any life-size dinosaurs to place around the city.

I’ve been all over Malta and I’ve seen your outdoor sets and I’ve seen the water tanks. I’ve seen everything. But I do think that the soundstage is key, so people can do interior filming as well as exterior filming. So realistically, we’re now in June of 2025; what is your most optimistic goal in terms of when a soundstage could be actually functional on the island?

GRECH: My drive is that I want to build the soundstage today or tomorrow. From my experience, we are losing more work than getting work because we don’t have the soundstage. So the soundstage is fundamental in terms of giving a guarantee to careers in film. It will generate more jobs, and it will generate more careers. Now, what we are building is a world-class soundstage, which will be located near the water tank, which was built in 1979. So, the stage that we are building, which is around 45,000 square feet, it’s a huge stage, will also hold the water tank, so you can have an asset inside the tank inside the stage. When you open the elephant door of the stage, you will see the horizon of the sea. So, it will be quite unique.

CARTER: So you should do The Goonies 2.

It’s funny you say that, because they’ve talked about doing a sequel to Goonies, and I am curious. My take is if you have an amazing script, okay; if you do not have an amazing script, do not make this.

CARTER: Absolutely. And I’m not sure you can make an amazing script. But Back to the Future is the same way, and E.T.. I was just thinking about the idea of when we built a ship in a tank inside at Warner Bros. for Goonies. But if you have a stage here and you can do that, fantastic.

They need to build it, but hopefully soon.

GRECH: It will take two years. What I can say is that there is the determination and commitment from the government. The last investment in the film studios was made in the 1980s, and unfortunately, that investment then stopped short. When I became a film commissioner, I lobbied my government that now it is the real time to invest for the next 100 years. The benefits of our water tanks, which are unique globally and known globally, were built in 1964 and ‘79, respectively. We still are reaping those benefits. We are still reaping those dividends. So, the stage that we want to build is built based on a vision for the next 100 years. We want to make the next 100 years better than the first.

It’s funny how many people I speak to when they’re talking about water tanks are always like, “We went to Malta for the water tanks.”

The Mediterrane Film Festival Continues to Expand Its Industry Reach

“It’s an opportunity between countries to use the festival as a platform to discuss ideas, to discuss collaborations together, to see how we can co-produce stories together.”

I want to switch to something else, which is the Mediterrane Film Festival. It’s now in its third year.

GRECH: Bigger and better.

I’ve been here all three years, and the first year was good, last year was better, and this year is even better. Why is the festival important to Malta, and how do you envision the festival in, say, five years from now?

GRECH: It’s a tool. The festival, apart from all the objectives that we have, is a business tool to get more business to Malta, to our island. As I started a film commissioner, I told you that it’s all about business, and it’s all about marketing, and it’s about shaping and reshaping our product. For us, this is an important moment where we invite people like Rick and producers and directors and other production designers and filmmakers and studio executives, those who make the decision to shoot in different countries. For us, the Mediterrane Film Festival is a tool for our key audience to, in a tangible way, see our product, imagine their stories, and how we can service those productions, apart from other objectives, which are also it’s an opportunity between countries to use the festival as a platform to discuss ideas, to discuss collaborations together, to see how we can co-produce stories together. So, I think in this third edition, apart from increasing awareness about the film industry and increasing awareness about the art of film on the global stage, I think that we are meeting all our objectives.

Designing the Future for ‘Back to the Future II’

“Where we’re going, we don’t need roads.”

I love the Back to the Future movies. You worked on the second and the third, and I’m curious, what is it like designing the future? I saw it when I was young, and to me, I think it’s like 15 minutes of the film or 20 minutes, but it meant a lot to me because it was the Back to the Future version of the future. Can you talk a little bit about collaborating with Zemeckis and what that film meant to you?

CARTER: I’d like to actually take that question, if I can, and I’m going to try to tie it into what you were just saying about the festival, but my take on it. First of all, working with Bob Zemeckis and Bob Gale in those days, coming off of Back to the Future that they’d already created with Larry Paull as the production designer, created a wonderful backlot set that was two time periods, the 1950s and 1985. So, I was coming into that, but I’m coming literally into a process that is described as, “Where we’re going, we don’t need roads.” Okay. Where are we going? We’re really going to go somewhere. We know what it is, but we don’t know where to look, except that both Bobs, Bob and Bob, would say, “This needs to be an optimistic future. This is not a dystopian Blade Runner future.” The problem is with Marty McFly’s decisions in life. That’s what the whole movie is about is how he plays out his life, not that the world is a problem. So, how do we make it appear optimistic? One of the ways was to actually have it be balanced with nature, so the idea to put a Japanese pond in Courthouse Square was quite a radical idea, really, for the time, but also the commercialization. So there was a vibrancy to the commerce of Hill Valley, and not to make it too overwhelmingly large, or having grown out of proportion. So, to project ourselves there into that world was wide open for the team and myself that was able to create that.

Then on top of that, if you think about it, with time travel, you come back and something that’s happened in the future — which is backwards for how normally people think; you think something in the past is affecting the future — has now impacted your past, and you can’t come back to your home. It’s like going to Oz but not being able to get back to Kansas. Now, Biff has taken over everything, and Biff is Donald Trump. That’s what he’s modeled after. Everything is right there to be seen. That was the actual prediction of Back to the Future II even though that’s not where you’d think the predictions of the future were. It’s the whole movie. It was, in time, kind of drifting in and out because you then went to the ‘50s and then had to go all the way back into the 1880s in order to solve the issues to be able to come back and have your present tense be okay.

That is quite a wonderful travel experience because it’s time travel. That’s Zemeckis. He’s played that out throughout his life. It was a fantastic introduction for me. All the movies I’ve gotten to work on go to different places, time periods, genres. It’s a mix. Malta is a mix. But I’m just going to comment to you that your film festival is more than a tool for your finances. It’s how you identify to the world who you are and lead with what you already have, which is an identity quest. The identity quest is embedded in your culture and in all the time periods, and when people come here, they get lost a little bit, but they like the feeling. It’s like going to Back to the Future. You walk down and you say, “Look where we are. What happened in this room? What am I experiencing?” It doesn’t just happen everywhere, and certainly in other places, it might all be locked into one huge battle between this group and this group. You have big battles that have happened culturally and historically, but culturally, you’ve had this influx and swirling, and what I’m saying is that is why Malta is unique. That’s what you can project through your film festival out to the world. This cannot happen anywhere else like this, with such ease of cultures. You’re used to it.

So while it’s a tool for your production, I understand the economy, that’s the half of what I have to do as a production designer — bring it on budget, schedule everything — but what is it? What’s going to cause people who want to have a part of it and pay tickets for it? I would just want to encourage that, that you see what you’re already doing and then let that kind of explode in your head and out of your head to all the people that are here, and present that message. So, on Sunday night, don’t make this third one, “Well, we’re kind of doing this, and we’re sort of doing this.” The third time’s the charm. You brought all these films together, a jury came in and thinks maybe this is the best, but that’s not the way to think of it. It’s fine that all those groups of people who participate get a prize, and they can work with that, but it’s a celebration of the cinema of the area, or the filmmakers that came from here that went somewhere else on a few of the movies. What I’m trying to get at is that’s what I discovered. That’s what everybody on the jury discovered when we went into those screenings, and one after another were taken to various places and states of mind around the Mediterranean. It’s why it’s called the Mediterranean. Define the Mediterranean as you want to experience time, places, history, anything, you can do it in Malta.

GRECH: You’re right.

CARTER: That’s a production designer’s point of view.

GRECH: You are saying it. Yes, it’s a small country, but we are very rich in history and culture.

CARTER: And vision.

I’m very curious what’s going to win the Jury Prize. We’ll find out Sunday.

Filming Outside the United States Serves a Greater Purpose Beyond Finances

“You build worlds.”

You touched on Trump a little bit, and I definitely have to bring it up. How nervous are you about the tariffs that he’s talking about? Personally, I don’t understand. I understand if you are manufacturing a clock in China instead of the United States, okay, a tariff, whatever, but how do you put a tariff on a movie? It doesn’t make any sense. How do you film in the United States, Malta? That doesn’t add up to me. It’s illogical.

CARTER: It’s not a product like that. It’s not a thing. It’s an experience that has components that bring it together, and they’re coming from all sorts of, like the finances and who’s doing it. But if the purpose of the adventure is to take you out of your theater seat or your home theater and the TV to a place you’ve never seen, that expansiveness can’t just happen anywhere. That’s why I’m saying this place offers up something that is a kind of backlot for your imagination in time. I’ve done this. This was my job. I stand here, and I go, “That can be Paris.” I’m auditioning the locations. “Who wants to raise their hand? Okay, you can be Paris.” But I don’t want to have to move the trucks all around, day after day after day, all over. We’ll move them plenty. But, “You’re Paris. This thing looks like it could be this scene.” Or, “You’re Israel right here. That could be Palestine right there.” Then you’re actually doing something that is magic. It’s cinema. I’m just bringing those two together, and there’s no war. I’m here. We can park the trucks here and shoot both of those, and both groups will go, “Yeah.”

Or you go into a stairway, as we did, and say, “There’s a place that nobody owns.” It has a presence that defies the logical, binary way of thinking that there’s only this or that. You can use locations to be what they need to be, as long as they’re associating and, in a sense, visually speaking to the other one. Now there’s a contrast, and you can build this, this, this, that, this, this, this. When I get to seven, I’m going, “Okay. Well, I guess that’s all. The rest we’ll figure somewhere else.” But you have a production. Now they can say, “Okay, we know how to budget that.” That’s coming from the vision.

What I’m saying is that I understand tariffs on certain things, but I do not understand tariffs on movie-making and television shows. When certain storylines call for you to film around the world, how do you recreate that in America? It doesn’t make sense.

GRECH: I’m all for collaboration and cooperation. Our key markets are America and the UK, and other European countries. 70% of our work comes from America and the UK, so we have to be prudent on this talk of tariffs; it’s all about incentivizing business. I totally understand that different states in America want to incentivize business from businesses, and it’s right to incentivize business. So, this is more about incentivizing business rather than taxing business.

CARTER: And also providing the vision that will actually get people to see whatever they’re looking at in the entertainment as something that does transport them, so they can actually believe something about going to wherever they’ve gone to. Everything’s not surreal and fantasy and the computer. You feel something, and that’s what you get from being here.

GRECH: And talking about vision, your vision, you don’t just build it and create sets and design sets. You build worlds. So, back to the vision of Rick, it is so important that our vision is clear with objectives for the future.

CARTER: Well, an island in the middle of the Mediterranean of your mind is a good place to be.

Stanley Kubrick and Steven Spielberg Share Their Dream With ‘A.I. Artificial Intelligence’

“We collaborated and built tremendously upon what Stanley had done.”

I’m a big fan of A.I., which Kubrick came up with and Spielberg took over. Kubrick designed 600-something or 700 images for his version of the film. When Steven took over, a lot of what Stanley came up with is in the movie, and then, obviously, Steven came up with other things. I’ve always wondered how many of those drawings that Stanley had, that I’m sure you saw, actually ended up in the movie.

CARTER: The concept of A.I. and the treatment from Stanley of this Pinocchio consciousness story that is artificial intelligence, but it’s our intelligence going into the future, in a four-act structure that was Stanley’s, and Steven wanted to be true to what Stanley had done. Chris Baker, who was this incredible artist, worked with Stanley to create a kind of visual roadmap through the movie that they envisioned. Now, there were lots of gaps, but there were so many fundamentally wonderful things that you absolutely would be crazy not to just celebrate and go as far as you can with. So, I arranged to have Chris come over to be a part of the art department, and then we collaborated and built tremendously upon what Stanley had done, and that involves some of the iconic imagery from the movie — the Flesh Fair and particularly Rouge City, and the way things were designed with circles throughout the movie.

I could go on a whole thing about what the movie design was, but the essence, that DNA, came from Stanley, and then Steven brought it to his. People like to divide it up as though Stanley is the mind and Steven’s the heart. How intelligent can a heart be, and then tell a story of a little boy who’s actually not human and loves his mother, and wants to be loved by his mother, and to be able to dream? It’s a very wonderful fairy tale. I still think it’s amazing the serendipity that this idea of AI that Stanley conceived of, and even structurally with four acts… Same as 2001; the fourth act of 2001 is to infinity and beyond. That’s exactly what happens in AI 2000 years into the future. Here we are, 20-something years in the future, and we’re kind of in the Flesh Fair version of the introduction of AI into our lives, because look what it can do. If you look at that scene, and then you hear people rant and rave about AI, I’m not saying they’re wrong, I’m just saying the roadmap has already been laid out as to what we’re experiencing.

Related

‘A.I.: Artificial Intelligence’ Is the Essential Pinocchio Film of Our Time

Steven Spielberg’s ‘A.I.: Artificial Intelligence’ is a masterful, yet criminally underrated, rendition of the Pinocchio story.

A lot of people don’t realize the last 20 minutes of the movie is all Stanley. A lot of people think that might have been Steven, but it’s all Stanley.

CARTER: It’s actually both, because the key is they both deeply, deeply love their mothers and got so much from their mothers. You can’t tell that story if you don’t. They both did. The conveyance of that emotion and the need to be able to get there and feel the reciprocation, and have one perfect day that allows you to be — and it is the dream — that’s their shared dream.