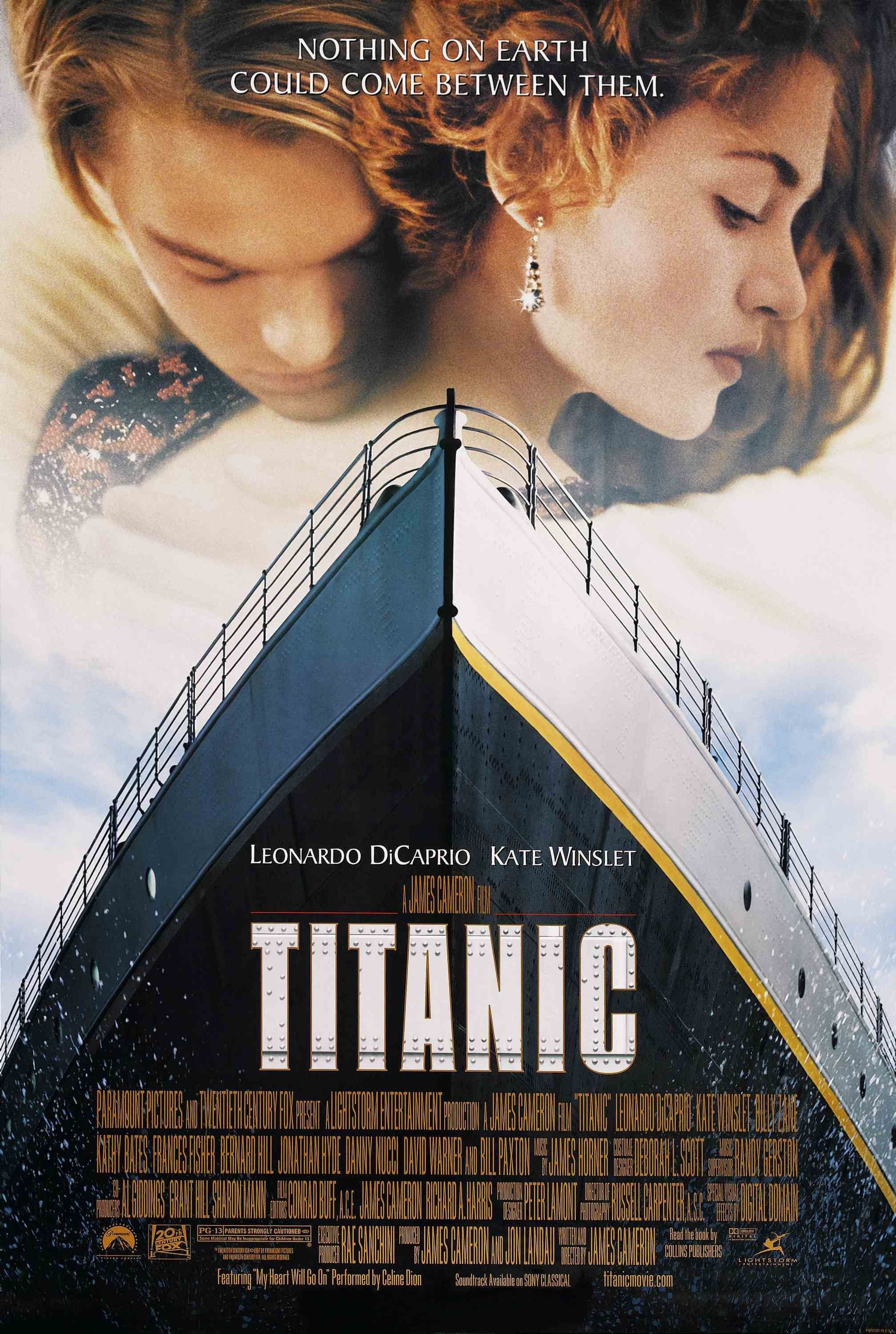

The public packed movie theaters in 1997 and early 1998 during Titanic‘s historic run at the box office, which became the highest-grossing film in history until James Cameron outdid himself in 2009 with Avatar. As a sweeping romantic epic crossed with a high-octane disaster spectacle, the film, which eventually won the Academy Award for Best Picture, appealed to everyone on both an emotional and cerebral level. However, Titanic was not exactly renowned for its writing or characterization, with some people mocking it for being too broad and maudlin. Cameron’s erroneous reputation as a poor writer began with the film that announced him as the king of the world, and his perceived weaknesses behind the page originate from his embellished portrait of the stuck-up socialites in Titanic. However, one emotionally resonant scene between Rose (Kate Winslet) and Ruth DeWitt Bukater (Frances Fisher) humanizes the folks deemed inhumane.

James Cameron Villainized the Upper-Class in ‘Titanic’

Titanic is many things—endearing, thrilling, and the grandest of cinematic achievements, but what it isn’t is subtle. Because he directs movies for the widest audience across the globe, James Cameron often deals with the starkest emotions and sensibilities, which leads to caricatures of villainous forces. Before Giovanni Ribisi played the embodiment of evil imperialism in Avatar, the titular fateful ship sailing across the Atlantic Ocean showcased the class divide in the most simplistic mode. In short, the upper-class, uber-privileged passengers on the ship were snooty, selfish, staid, and insular; the lower-class, downtrodden passengers were caring, hard-working, and full of heart. This dynamic is our general view of the class divide, but Cameron lays this on thick.

Related

The 10 Worst Movie Villains Who Were Just Misunderstood, Ranked

Bring back villains who are just pure evil.

The suppressive Gilded Cage is what causes Rose, who is set to marry the heir to a steel tycoon, Cal Hockley (Billy Zane), to run away from her wealth and influence and pursue her true love, an impoverished but dashing migrant with a gift for art, Jack Dawson (Leonardo DiCaprio). The only people more swept up by Jack’s romanticism were viewers in 1997, as it launched DiCaprio as a global icon. As is the case with any classic love story, audiences detest anyone who tries to prevent this natural fling from following through. Not only do Rose’s family not understand why this privileged girl with the entire world at her fingertips is depressed, but they can’t fathom that she would stoop so low as to live in the perceived gutters of society.

The Corset-Lacing Scene in ‘Titanic’ Humanizes Ruth DeWitt Bukater

Rose’s mother, Ruth, rivals Cal as the most loathsome character in the film. Sharing all the uptight sensibilities of her contemporaries, she expresses little interest in her daughter’s innate desires, and only uses her as a pawn to further her family’s wealth and connections. But across the film’s three-plus-hour runtime, one scene between Rose and Ruth, where the mother laces up her daughter’s corset, upends all character dynamics and changes my way of thinking about Ruth altogether.

Aggressively tightening the laces of her daughter’s dress, Ruth insists to Rose that she never come into contact with Jack again in her usual stern demeanor, but the soon-to-be young wife isn’t having any of it, remarking “You’ll give yourself a nosebleed,” regarding her rage. Once again, Ruth makes it about money, something Rose is tired of hearing about. As she lectures Rose, Ruth sounds less like a stick in the mud and more of a cautious, supporting mother, as she reveals the sobering realities of the DeWitt name. If Rose doesn’t marry Cal, their legacy and their wealth evaporate.

“Why are you being so selfish?” asks Ruth, an ironic statement that appalls Rose, but this scene places us in the socialite’s shoes. “Do you want to see me working as a seamstress?” Coincidentally, the act of lacing up Rose’s corset reminds Ruth of the alternate lifestyle she will inhabit if this planned marriage follows through. This isn’t meant to put down working labor, but rather, a reminder that their luxurious world will crumble. Ruth asks her daughter if she wants “to see our fine things sold at auction” and “our memories scattered to the winds.”

Despite all the excess of wealth and resources, Rose is stuck in this suffocating catch-22. To secure the family’s best interests, she must not follow her heart. “Of course it’s unfair, we’re women,” her mother reminds her. This humbling and poignant scene rejects any notion of James Cameron as a shoddy screenwriter, as it grounds the antagonistic Ruth and makes us wholly sympathetic to her struggles that she can’t express to the outside world. At the end of the day, the greatest disparity of all is not the class divide but the gender barrier. Women are expected to be trapped in rigid social spheres and merely serve as nurturers for the family name. While the mother and daughter clash throughout the film, their lack of social liberation makes each of them feel seen, and puts them on more of an even playing field.

Like the framework of Titanic, which juxtaposes an intimate romance with one of the most infamous disasters of the 20th century, there is more at stake with Rose’s seemingly harmless fling with Jack. By following her heart, she might erase the legacy of her family name, and this scene makes us truly understand why that is such a terrible prospect to Ruth.