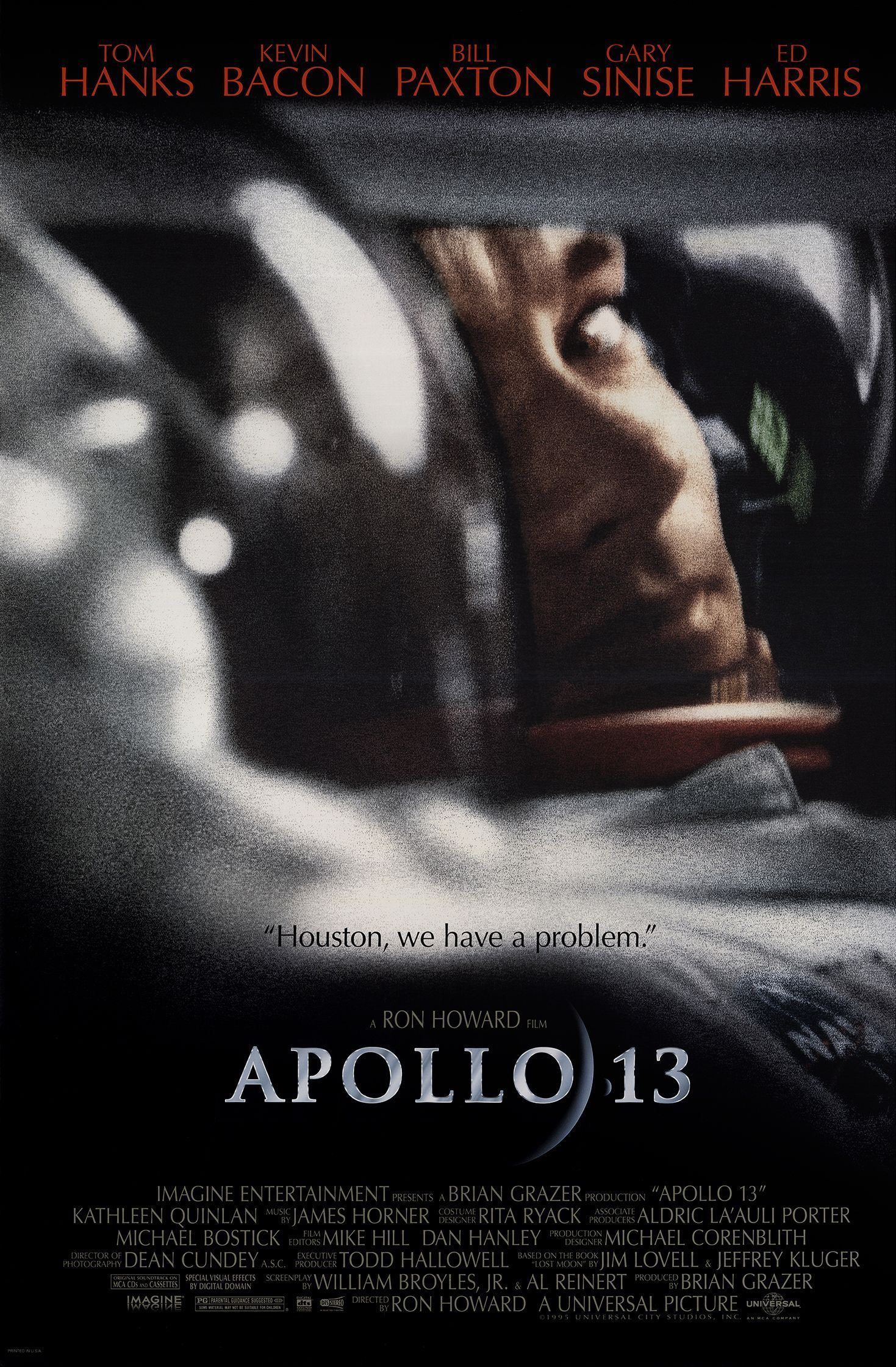

There is arguably no greater range of genre than the space film. The action of the Star Wars films, the horror of Alien, the comedy of Galaxy Quest, or the suspense/WTF of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Real-life events, too, have been dramatized for the big screen, like 1983’s The Right Stuff, which detailed key events before and during NASA’s Mercury space program. But none have done it better than the Ron Howard and Tom Hanks collaboration that’s turning 30 this year: Apollo 13, the 1995 modern-day classic that stands as the best space film ever made.

‘Apollo 13’ Dramatizes a Near-Disaster That is Unbelievably True

The difference between a film like The Right Stuff and Apollo 13 is this: plausibility. Given that both detail true-life historical events, it’s an odd statement to make. A true-life account is plausible by its very definition because it happened. But it’s the perception of plausibility that separates the two. The Right Stuff tells a real-life story about things that actually took place, things that one can believe actually happened. Apollo 13 tells a real-life story about an event that took place, but it’s an event that borders on the unbelievable, a story that one would swear was created in Hollywood and not in a cramped lunar module miles above the Earth.

That “it can’t possibly be true” element is one of the film’s greatest assets, adding a degree of awe to its driving sense of urgency, of consequence. It also helps that Apollo 13 details an event that had been largely forgotten, or flat-out ignored, standing as a blemish on NASA’s space program history for the longest time. Seeing the reality behind the incident, a never-ending assault of problems that can’t possibly be solved but need to be — and are — gives Apollo 13 something more than just credibility: it brings respect for the heroes on the ground and the three up above that made the impossible possible. That respect, earned by the film’s detailing of human ingenuity, improvisation, and quick decisions, helped cement the narrative of Apollo 13 as a “successful failure” as opposed to the initial assessment of it being NASA’s worst disaster.

‘Apollo 13’ Is a Testament to the Power of Accuracy in Film

Of course, in order for Apollo 13 to maintain the awe and respect that comes from watching the impossible possible, the details of the incident can’t be overtly embellished or made up. The Battle of Stirling Bridge in Braveheart looks great on film, but disrespects the reality of the battle by attributing its planning to William Wallace (Mel Gibson), and by not having a bridge, let alone Stirling Bridge, anywhere in the scene. That isn’t an issue with Apollo 13. The film largely sticks to the facts, and where it doesn’t — the control room was much less chaotic, with a contingency plan already in place for emergencies — it adds a relatability that elevates the emotional urgency of the event, without sacrificing the truth behind it.

Related

The 10 Best Movies Directed by Ron Howard, Ranked

Opie Taylor grew up to be a highly respected director.

That makes it a great film about a historical event, but not what makes it a great space film, and that’s where the accuracy of the film really stands out from the pack. Instead of relying on CGI or dodgy wire techniques to simulate zero-gravity, director Ron Howard took an unconventional route by having his actors and crew work in zero-gravity conditions for an authenticity that is above its space film kin. That involved spending time aboard a KC-135 airplane, aka “the vomit comet,” achieving about 25 seconds of weightlessness at a time by flying in a parabolic pattern, ascending to 36,000 feet and then into a steep dive. NASA was reluctant at first to cooperate, but finally gave permission to Howard (with a little help from Apollo 13 astronaut Jim Lovell himself), under the condition that the film’s actors and crew undergo several days of training, take a written exam, spend time in hyperbaric chambers, and take a test flight to prove they could “cut it.”

Scenes were rehearsed and choreographed on a mock-up set on terra firma before taking flight, with motion sickness held at bay (with a few exceptions) with a cocktail of Scopolamine and Dexedrine. Filming the zero-G scenes could only happen during that 25-second period, and it would take 612 parabolas to come to about four hours of footage. The footage was augmented with scenes filmed using practical techniques to simulate weightlessness, like “belly pans,” a seesaw device that moved the actors up and down. Having been accustomed to performing in actual zero-gravity conditions, they were able to mimic what they learned aboard the KC-135. The result is an expertly edited, seamless depiction of actual weightlessness that is timeless, unable to be victimized by outdated CGI effects that have proved ruinous for others.

‘Apollo 13’ Finds Success on the Back of Its Director and Cast

But accuracy alone doth not a great space film make. 1997’s Contact was cited by NASA as being one of the most accurate, but rocks a less-than-stellar 68% on Rotten Tomatoes. Apollo 13 has the benefit of a director at the top of his game and a cast that excels. Howard deftly makes subtle, effective changes to the story that engage the viewer. For instance, summing up the real-life exchange between the astronauts and Houston in five chilling words: “Houston, we have a problem.” The decision to film in zero-gravity, which earned Howard a “You’re crazy. I never thought you’d really do that” from Steven Spielberg, was savvy. Howard also frames the film so that we as viewers experience that claustrophobic feeling aboard the lunar module, an unsettling feeling that adds to its urgency.

Ed Harris brings a steely resolve to Gene Kranz, a determination to bring the astronauts home that supersedes the impossibility of the task. Gary Sinise captures the disappointment of Ken Mattingly in being taken off the mission, and his valiance in putting that aside to help find a solution to bring his friends back. Both Kevin Bacon and Bill Paxton are excellent in their roles as Jack Swigert and Fred Haise, respectively, capturing the angst of their situation to perfection. And Tom Hanks does what Tom Hanks always does: shine. He’s the Everyman in the unenviable position of being thousands of miles away with little hope of returning home. You can see the fear in his eyes, the agony of seeing his dream of landing on the moon unceremoniously taken away, the glimmer of hope when all hope is lost. In a movie that stands unrivaled as the greatest example of a space film, Hanks is the cherry on top.