The world can be an unfair place, for reasons that are probably clear to anyone living in it, and so it stands to reason that some movies should explore the ways it can be unfair. Some films function as escapism, sure, but then the ones that want to look at the harsher sides of life get a bit more cynical. Such movies aren’t without entertainment value, but they are considerably heavier, and maybe best watched only when one is feeling up to it.

The following movies might not be the most shocking or even the most depressing of all time, but they do feel like they can be counted among the most cynical (plus, some are shocking and/or depressing). There are probably other films that are equally cynical to these, and the following ranking can only include so much (this could be dozens, or maybe even hundreds of titles long), and maybe that’s just another unfair reality of life.

10

‘Brazil’ (1985)

Directed by Terry Gilliam

While Brazil is sometimes funny, and just about always visually dazzling, it’s also a tremendously upsetting and downbeat take on the science fiction genre. It follows one man who has his life spiral out of control in a way that, at first, feels kind of farcical, but then the escalation of it all pushes past the bounds of comedy, and Brazil eventually feels more like a nightmare.

If there’s a central message here, it’s that the world is chaotic, disorganized, and cruel, and becomes more so, seemingly, the more humans try to organize and regulate things. Aesthetically, it might not feel like a prophetic movie (as of 2025, very little in real life looks like the locations in Brazil), but thematically and emotionally, it might well have been ahead of its time, in looking forward and capturing a sense of life getting more out of control, the more time passes.

9

‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ (2013)

Directed by Martin Scorsese

As a director, Martin Scorsese likes to keep things pretty real, and so singling out just one of his movies as his most cynical feels difficult. There are at least several that could be counted here, so honorable mentions ought to be given to Raging Bull, Casino, The Irishman, and Killers of the Flower Moon, just for starters. But it’s one of his most entertaining films that might well be his most cynical: The Wolf of Wall Street.

This is a film that’s a good deal of fun at times, and much of it plays out like a comedy, though things collapse and get a bit heavier in its final hour, especially when it comes to depicting the more harrowing parts of Jordan Belfort’s personal life. But, in the end, Belfort isn’t really held accountable. He’s too powerful, and then The Wolf of Wall Street has an ending that suggests countless people out there would want to be him, if they could. It’s a movie about how being good doesn’t pay, and being bad can – once enough power/wealth is accumulated – eventually lead one to charge through life like a gamer using a handful of cheat codes.

8

‘Aguirre, the Wrath of God’ (1972)

Directed by Werner Herzog

Aguirre, the Wrath of God is technically an adventure movie, but not a fun one. The titular character leads an expedition through the Amazon in search of the lost city of El Dorado, but so little goes to plan that one starts to wonder if there even was a plan to begin with. Death, continuing madness, and perpetual discomfort ensue.

Aguirre, the Wrath of God has undeniable visual beauty that contrasts with all the harrowing stuff going on narratively and thematically.

It’s a Werner Herzog movie through and through, and calling it one of his most downbeat and cynical about human nature really is saying something. But, even with all that, Aguirre, the Wrath of God is still quite compelling, and it has undeniable visual beauty that contrasts with all the harrowing stuff going on narratively and thematically, so it ends up being an arthouse classic for sure.

7

‘Sunset Boulevard’ (1950)

Directed by Billy Wilder

If you’re talking about cynical movies and don’t mention at least one that counts as a film noir, can you really say you’re talking about cynical movies? The classic film noir period lasted throughout the 1940s and 1950s, and pretty much all of them were visually/atmospherically moody, narratively intense, morally murky, and pessimistic about human nature and the world at large.

Of all the classic film noir titles, Sunset Boulevard might well be the best of the best. It’s a movie that uncompromisingly looks at the film industry and lays bare how hellish it can be, both for older individuals who’ve been discarded, and for younger people who want to make a name for themselves in the scene. Unhappiness is found throughout all of Sunset Boulevard, but it’s cynical in a way that’s genuinely entertaining, and also oddly funny at times, too, if your sense of humor is dark enough.

6

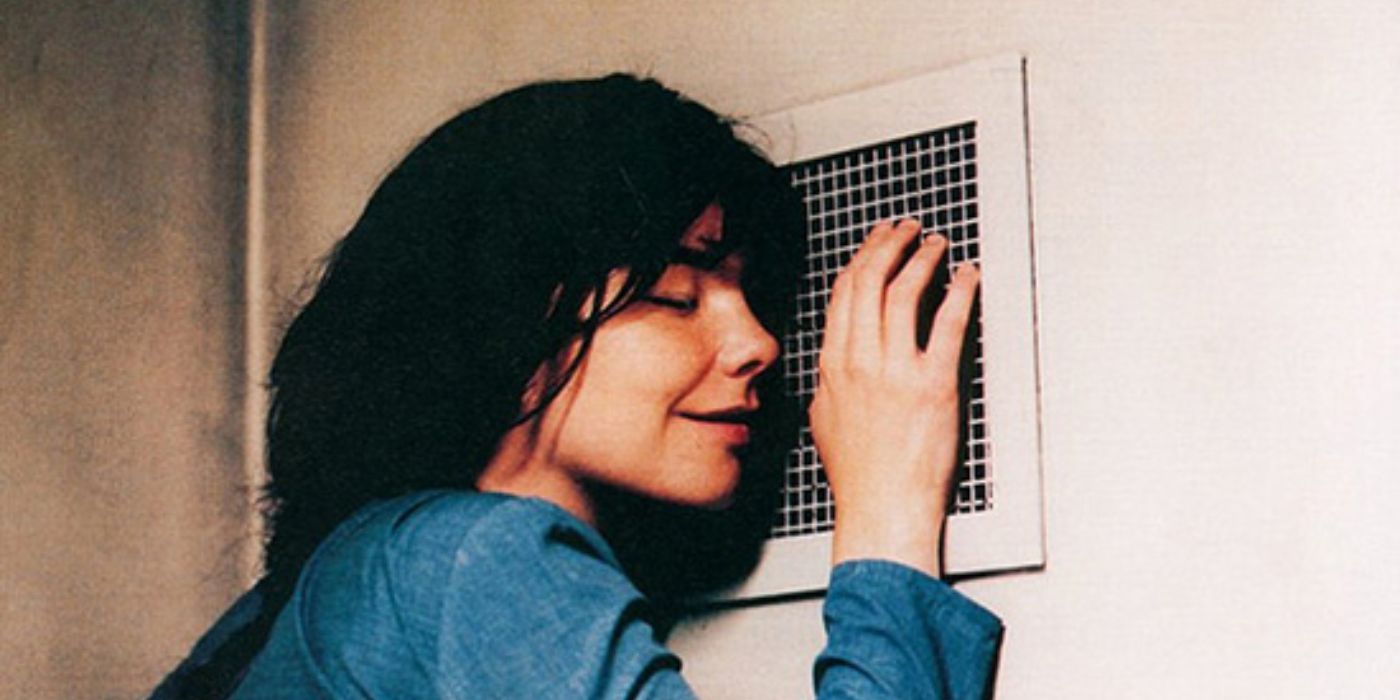

‘Dancer in the Dark’ (2000)

Directed by Lars von Trier

If you don’t mind oversimplifying things a bit, Dancer in the Dark is essentially a movie about one person’s life being so difficult that they continually retreat into fantasies, all of them shown as elaborate musical numbers. Björk gives a remarkable performance as that tragic figure – a woman named Selma – who has a physically demanding job, is going blind, and is determined to ensure her son doesn’t have to deal with such a condition once he’s older.

And that’s just the start of things, because about halfway through Dancer in the Dark, things go from bad to worse, and it all starts to feel genuinely despairing. It’s one of the most soul-crushing movies of the 21st century so far, or perhaps even of all time. Certainly, musicals don’t get much heavier or more heartbreaking than this one does.

5

‘Network’ (1976)

Directed by Sidney Lumet

Keeping a sense of paranoia high throughout, all the while pulling no punches in exploring how cruel the media industry can be, Network has a premise that no longer feels quite as heightened or ridiculous as it might’ve felt in 1976. The central premise here involves a news anchor having a nervous breakdown, thanks to an impending firing, and his erratic behavior is then exploited by the people he works for, given that his rants apparently make for good television.

Things just get worse for him, and while things might initially be “better” for the people doing the exploiting, there are eventual consequences for them, too (but not as many as for the anchor). All the while, Network doesn’t really let the viewers off the hook, either, considering people are curious – and do tune in – to see a man’s prolonged breakdown play out in real time. It’s disheartening stuff, especially because it all feels so prescient and unnervingly believable.

4

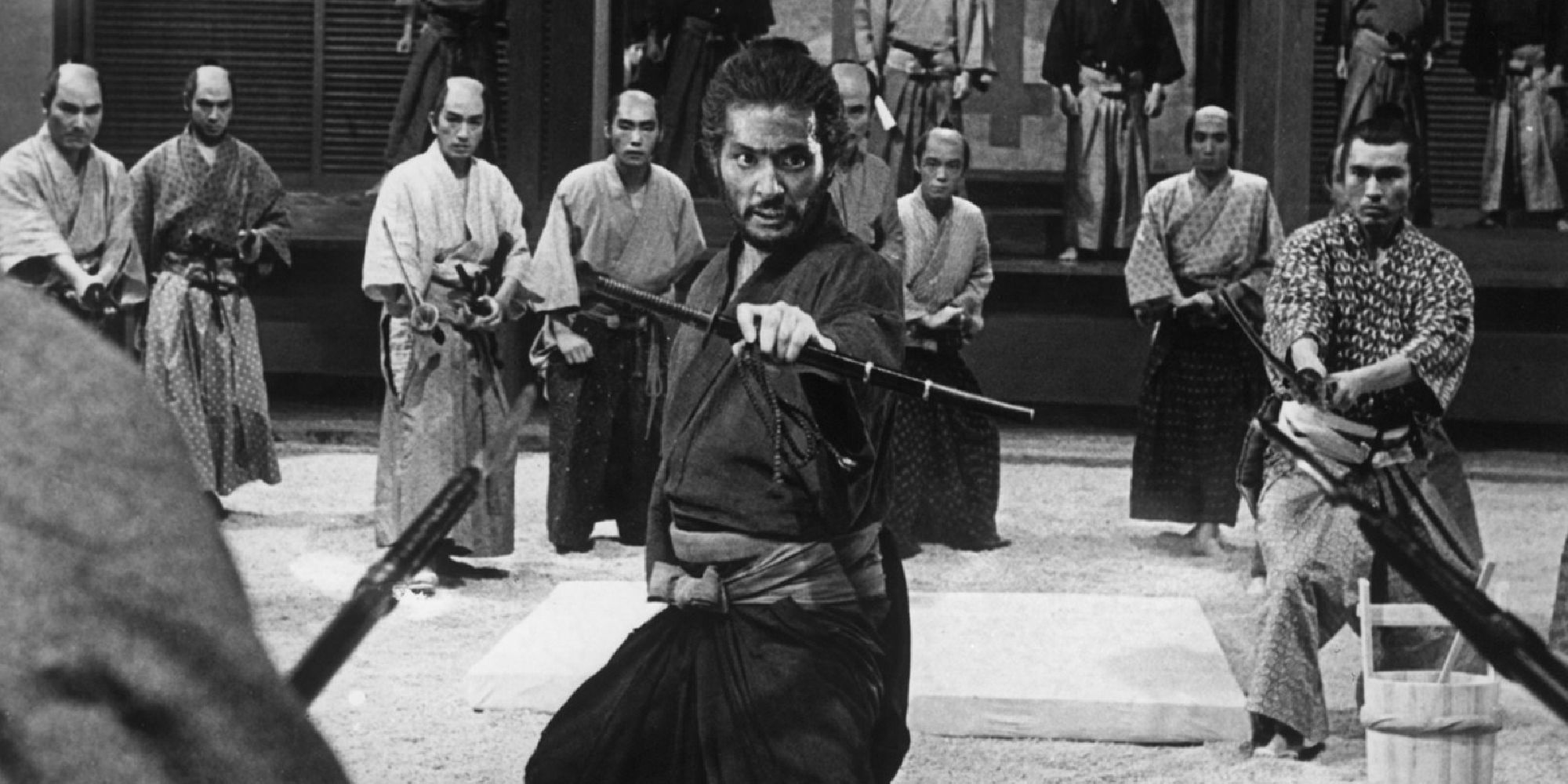

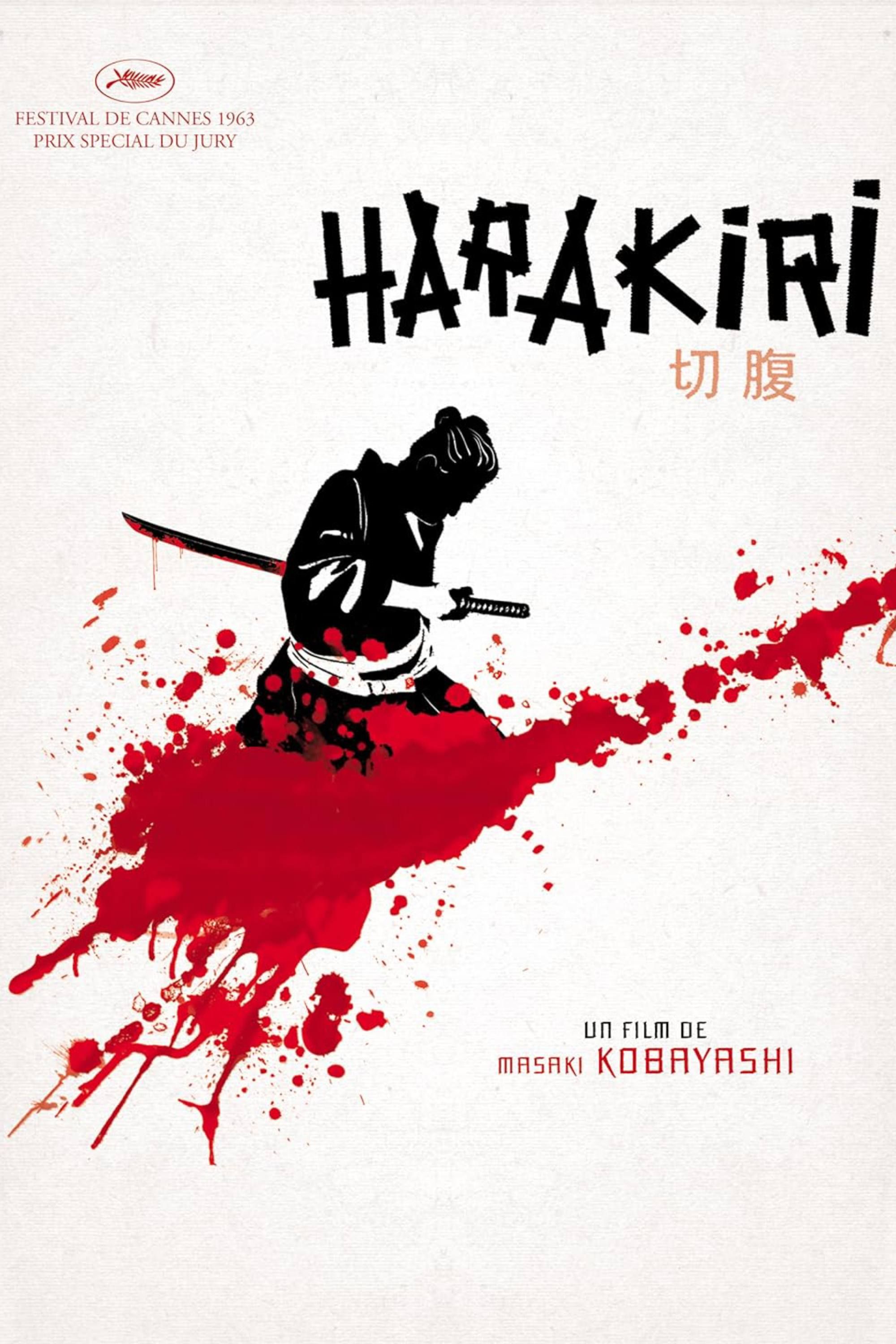

‘Harakiri’ (1962)

Directed by Masaki Kobayashi

Harakiri deconstructs various samurai movie tropes and conventions, and also functions as a takedown of the samurai, as a group, and their sometimes-assumed sense of honor. It’s about one man who’s had his life ruined by so-called honorable samurai, and he tells his emotionally intense story to a clan of samurai, after announcing his intention to commit seppuku, too.

Things already start bleak, given the protagonist expresses a desire to take his life right when the movie starts, but there’s so much more to Harakiri, and that heavy opening is really just the beginning. Even saying all that feels like it’s giving away too much, but then, at the same time, the intensity of a film like this can’t entirely be put into words, and one is simply better off experiencing it… so long as that person is ready for something quite slow and very sad.

- Release Date

-

September 15, 1962

- Runtime

-

133 Minutes

- Director

-

Masaki Kobayashi

- Writers

-

Shinobu Hashimoto

3

‘Fight Club’ (1999)

Directed by David Fincher

Another darkly satirical movie that balances humor and hopelessness, Fight Club is something you’re not supposed to talk about, but whatever, here it is. It’s great for all the reasons you’ve heard it’s great, with it capturing a certain kind of 1990s angst that still feels relevant and timely, even more than a quarter of a century on from the movie’s original release.

It’s a movie about alienation, rebellion, and, eventually, revolution, showing why those things are intoxicating yet eventually laying bare the problems that can come from rebelling, revolting, and fighting back against alienation too passionately. Or is it? Fight Club leaves quite a bit up to one’s own interpretation, but it’s hard to come away from it feeling good about the world and most of the people who live in it; that’s probably fair to say.

2

‘The Godfather Part II’ (1974)

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

1972’s The Godfather was certainly dark in places, but it wasn’t an entirely hopeless feeling movie. Some aspects of the mafia lifestyle felt romanticized, even if a great many hardships befell the Corleone family, and the film’s conclusion was ultimately one that felt quite tragic. But then in 1974, The Godfather Part II went even harder on the cynicism, becoming bleaker as a result.

There are breezier parts of The Godfather Part II, mainly with the flashbacks showing a younger Vito Corleone, but those sequences contrast brutally with the continued moral downfall of Vito’s son, Michael, who’s now running the family. That continuation of the story is much darker than the core story of the first film, and the way it stands out so vividly against the flashbacks ensures the whole thing is all the more impactful as a modern tragedy.

1

‘Chinatown’ (1974)

Directed by Roman Polanski

While Sunset Boulevard is probably the darkest of the original film noir movies, Chinatown makes it look positively sunny in comparison. This 1974 film could well be the bleakest and most cynical of all the neo-noir movies out there, pushing boundaries beyond what the film noir movies of old could do. It was made for arguably darker times, and thereby, it’s a much more desolate film.

Narratively, it’s recognizably noir, as Chinatown features a private investigator (Jack Nicholson) as its protagonist, and he tackles a seemingly simple case that, as it goes along, proves to be anything but simple. But the extent to which the corruption has spread, and the inability of anyone with a decent moral compass to do anything about the villains? That makes Chinatown feel far bleaker. Classic film noir movies often end with the bad guys and the comparatively “good” guys both losing, but here, the “heroes” are decimated, and the bad guy wins. And it’s not just that such a thing happens, but it’s how that thing happens that makes Chinatown perhaps the bleakest mainstream/relatively popular movie ever made.