Disaster movies usually leave us with a flicker of hope. Sure, there’s mayhem and destruction aplenty, but at least a few valiant heroes eventually make it out alive. There’s always a sense that the human spirit is unbreakable and can survive the toughest situations, even those that seem inescapable and positively apocalyptic. Not so in the following ten movies, though.

The disaster films on this list offer no triumph or catharsis, no last-minute saves or happy endings; no one gets away unscathed, and hardly anyone gets anything remotely close to salvation. Whether it’s the collapse of nations, the death of the planet, or the quiet unraveling of culture itself, these ten films show what happens when there’s no rescue, no redemption, and no will to rebuild.

10

‘2012’ (2009)

Directed by Roland Emmerich

“When they tell you not to panic… that’s when you run.” In the late 2000s, the whole “2012 doomsday prophecy” became a kind of meme and, for a small minority of people, a cause for some genuine concern. Roland Emmerich leveraged that idea into a big, gimmicky (and flawed) apocalyptic spectacle. 2012 dials the destruction up to 11, drowning continents, cracking tectonic plates in half, and sending giant fireballs raining from the sky.

Sure, a handful of characters survive aboard high-tech arks, but most of the world’s population is gone. Governments fall, faith collapses, and civilization ends. And unlike other Roland Emmerich films, the survival here feels hollow; bought by the rich, fought for by the few, and soaked in the blood of billions. Rather than a happy ending, we get an unearned extension of life for the lucky and the powerful. 2012 is dumb and weirdly nihilistic, but its implications are fairly intriguing: maybe we don’t deserve a second chance.

9

‘Deep Impact’ (1998)

Directed by Mimi Leder

“I know you’re just a reporter, but you used to be a person, right?” This one was marketed like a feel-good survival story. However, look closer, and Deep Impact is one of the most quietly devastating disaster films of the ’90s. A massive comet is on a collision course with Earth, and while a fraction of humanity is saved in underground shelters, most of the planet is obliterated, including entire coastlines and millions of lives. These scenes get surprisingly emotional, too.

The final minutes show families embracing on beaches, lovers saying goodbye, and a president (Morgan Freeman, terrific as usual) delivering a speech that manages to be simultaneously bleak and hopeful. The movie in general has a darker tone than these disaster blockbusters usually have (even if many performances are lackluster and some sequences fall flat). In Deep Impact, the comet isn’t vaporized or redirected. There’s no last-minute miracle, just a wall of water swallowing cities whole. Even those who survive emerge into a ruined world.

8

‘Greenland’ (2020)

Directed by Ric Roman Waugh

“My friend Teddy says your life flashes in front of your eyes when you die.” While Greenland follows a small family’s desperate attempt to survive a planet-killing comet, the film offers little comfort even to those who make it through. Most of humanity is wiped out. Every scene is laced with panic, cruelty, and desperate people realizing they’ve been left behind. Even when the Garrity family reaches the supposed safety of Greenland’s bunkers, they emerge months later into a ruined planet, smoke, silence, and ash where cities used to be.

Refreshingly, there’s no deus ex machina ending or heroic montage. What makes Greenland hit harder than other disaster fare is its emotional realism. Rather than being superheroes or presidents with hearts of gold, the protagonists are just normal people navigating chaos, clinging to each other, and barely making it. Overall, one of the more enjoyable disaster movies in recent years.

7

‘The Day After’ (1983)

Directed by Nicholas Meyer

“It’s only been five days, and I can’t remember what Bruce looks like.” Aired on TV in 1983, The Day After didn’t pull punches. It showed what would happen if the Cold War finally turned hot: nuclear warheads dropping on U.S. soil, entire cities vaporized, and the slow, grisly aftermath that followed. It’s a vision of radiation sickness, broken families, and the psychological death of a nation. The film was so terrifying that it reportedly caused nightmares, debates in Congress, and a shaken Ronald Reagan to reconsider nuclear policy.

That was the point. The movie was intended to frighten a complacent public. Every comforting illusion about survival is stripped away as society collapses not with drama, but with whimpers and confusion. By the end, even the survivors aren’t really living at all. For all these reasons, The Day After remains one of the most hauntingly realistic depictions of nuclear war ever put to screen.

6

‘The Mist’ (2007)

Directed by Frank Darabont

“You don’t have much faith in humanity, do you?” There are sad endings, there are bleak endings, and then there’s The Mist. Frank Darabont took Stephen King‘s already-horrific novella and twisted the knife, delivering what might be the most punishing finale in all of modern horror. Trapped in a supermarket by a mysterious fog filled with nightmarish creatures, the characters try to hold onto reason, but fear, paranoia, and desperation take over. Yet the real dangers are inside the building. There’s nothing worse than what people become when hope dies.

A woman becomes a religious fanatic, a father makes an unthinkable choice, and just when the horror peaks, just when you think it can’t get worse, the film unleashes a final gut punch so cruel that it leaves you in stunned silence. It’s a fantastically dark way to end the movie, a ballsy narrative choice that elevates The Mist above most entries in this subgenre.

5

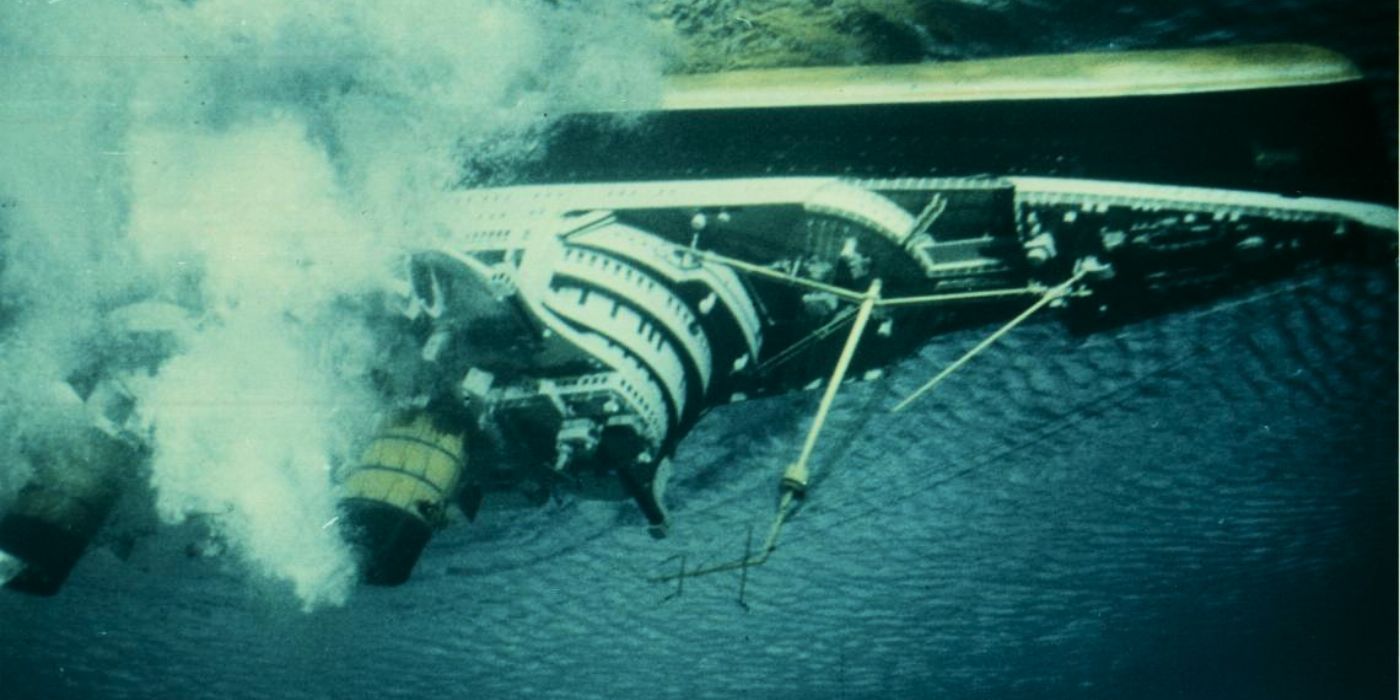

‘The Poseidon Adventure’ (1972)

Directed by Ronald Neame

“What more do you want of us?” A cruise ship capsizes after being hit by a massive tidal wave, turning a luxury voyage into a watery tomb. That’s the setup for The Poseidon Adventure, a disaster classic that set the tone for everything from Titanic to Deepwater Horizon. But unlike modern blockbusters, Poseidon never pretends things will be okay. The survivors are a ragtag group who crawl through flooding hallways, climb past corpses, and watch each other die one by one.

Even the ones who make it probably won’t ever fully recover from their experiences. There’s no sense of triumph to be found. Instead, the movie just gives you exhaustion and grief. Its power lies in how it treats death as inevitable, not exceptional. Nobody beats the ocean; nobody wins. There’s just a shrinking list of names and a slow crawl through a sinking steel coffin. This approach resonated at the time, and the movie was a runaway box office success.

4

‘Melancholia’ (2011)

Directed by Lars von Trier

“The Earth is evil. We don’t need to grieve for it.” A somewhat offbeat pick, Lars von Trier‘s Melancholia is less a disaster film and more a slow-motion funeral for the planet. The impending collision between Earth and a rogue planet named Melancholia unfolds like a dream. There’s no plan to stop it, no desperate mission to redirect the trajectory. Rather, the focus is on the varied ways people react to the certainty that it’s all going to end.

Some panic, some deny, some collapse, and one (Kirsten Dunst) quietly embraces the apocalypse, her depression eerily in tune with the world’s death rattle. All this adds up to one of von Trier’s grimmest projects, which is saying something. Here, the director conveys a lot through silence, stillness, and, most memorably, the stunningly composed final moments as three people sit beneath a fragile teepee of sticks, waiting for extinction.

3

‘On the Beach’ (1959)

Directed by Stanley Kramer

“Nothing worth remembering.” On the Beach is a nuclear war movie without a single on-screen explosion. By the time the film begins, the world has already ended; the northern hemisphere is gone, wiped out by radiation. All that’s left is Australia, waiting for the wind to carry death down to its final frontier. Here, a group of men and women are trying to live normally as the clock runs out. The tension comes from their calm, how quietly they prepare for the end. Some race cars, others fall in love, and a few simply wait.

There are suicide pills, tearful goodbyes, and haunting shots of empty cities. However, what makes On the Beach really work is the way it never flinches from its premise; the end is inevitable. By the time the screen fades to black, all that remains is silence and a banner flapping in the wind. On it is written: There is still time, brother.

On the Beach

- Release Date

-

December 16, 1959

- Runtime

-

134 minutes

- Director

-

Stanley Kramer

2

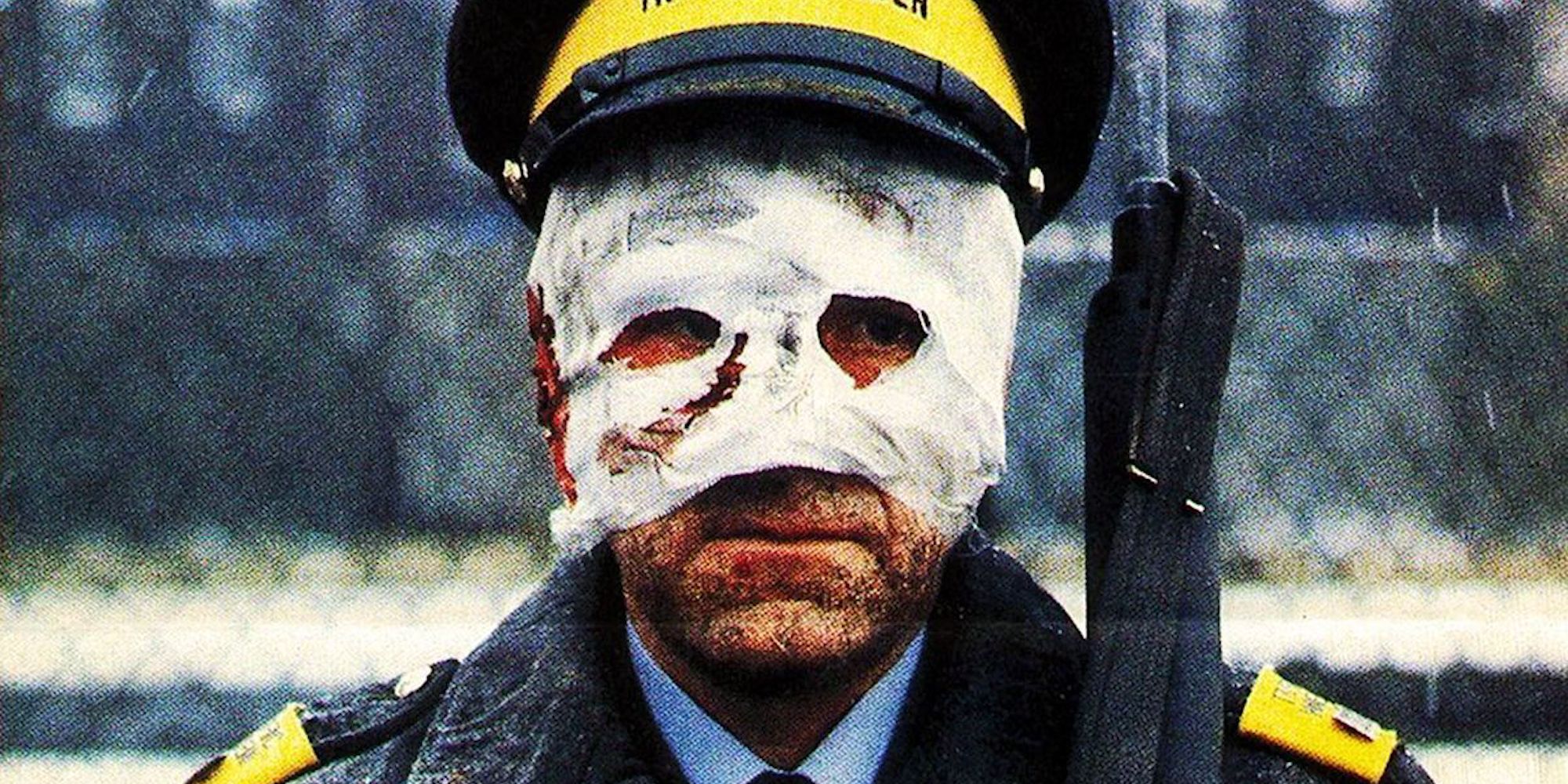

‘Threads’ (1984)

Directed by Mick Jackson

“Our lives are woven together in a fabric.” If you think The Day After was rough, try sitting through Threads. This British TV movie is the most harrowing depiction of nuclear war and its aftermath, period. In the wake of doomsday, there’s no order and certainly no rebuilding. Instead, the survivors must crawl through a world of disease, lawlessness, and starvation. Children grow up feral, and language erodes as humanity becomes something unrecognizable.

Millions of people die, but, perhaps worse still, culture, memory, and meaning die with them. Shot in a bleak, documentary style with minimal music and maximum realism, Threads plays like a warning that no one heeded. Like The Day After, it’s a cinematic trauma designed to terrify, and it works. A vivid depiction of the madness of nuclear weapons, a god-like technology that’s way beyond humanity’s emotional and moral capacity.

1

‘Contagion’ (2011)

Directed by Steven Soderbergh

“The average person touches their face three to five times every waking minute.” Contagion was already unsettling in 2011, but by 2020, it felt like prophecy. Here, Steven Soderbergh traces the spread of a deadly virus from a single infected bat through the global bloodstream, killing millions, overwhelming institutions, and unraveling every illusion of preparedness. Totally farfetched, right? The film is dry, clinical, and emotionally cold, refusing to give us a central hero or neat resolution. It’s a dark portrait of epidemiologists running models, loved ones being cremated, and economies collapsing.

Even when a vaccine is found, the damage is already done: the loss is permanent, the system has failed, and survival feels random. On top of that, there’s the uneasy knowledge that this wasn’t a one-off; it could happen again. In a genre obsessed with thrilling spectacle, Contagion cuts deeper by being completely plausible. Years ahead of its time, this remarkably prescient movie is one of Soderbergh’s very best efforts.